Favourable news coverage is not a ‘great outcome’ – so let’s stop calling it that

I’ve decided to start this blogpost with a cranky headline. Much like Dr Bruce Banner before turning into The Hulk in the first Avengers movie, I will also let you in on my secret: despite not showing it, I am always angry… whenever I hear someone call news coverage “a great outcome”. It’s not… And calling it that can cause us to drift away from our objectives.

Don’t get me wrong, favourable news coverage does make me happy, especially whenever my team and I have been working hard to attain this. My point is the outcome of our PR strategy and activities – the actual communication outcome – is something that can’t be seen in any news coverage analysis. Positive coverage does not automatically mean positive reputation. That is a far-fetched assumption, especially if we’re only looking at earned media to asses reputation. To understand the outcomes of our campaigns, we must look beyond.

To begin with, communication happens not when news is published or advertising is displayed, but when our target market reads or listens to what we say or is said about us, and when they understand, accept or respond to the stories that involve us. Likewise, it also happens when we listen, understand, accept or respond to the messages from our target audience – that is, if we accept the notion of stakeholder capitalism.

But even if we are still passionately attached to the old paradigm of shareholder capitalism, where the sole role of PR is to persuade a target market to think or act in a desired way about a brand or product, the real communication outcome can mostly be observed through market research, using techniques such as surveys, focus groups and in-depth interviews, among others, not by running news coverage analyses and making fancy-looking graphs with the clips achieved.

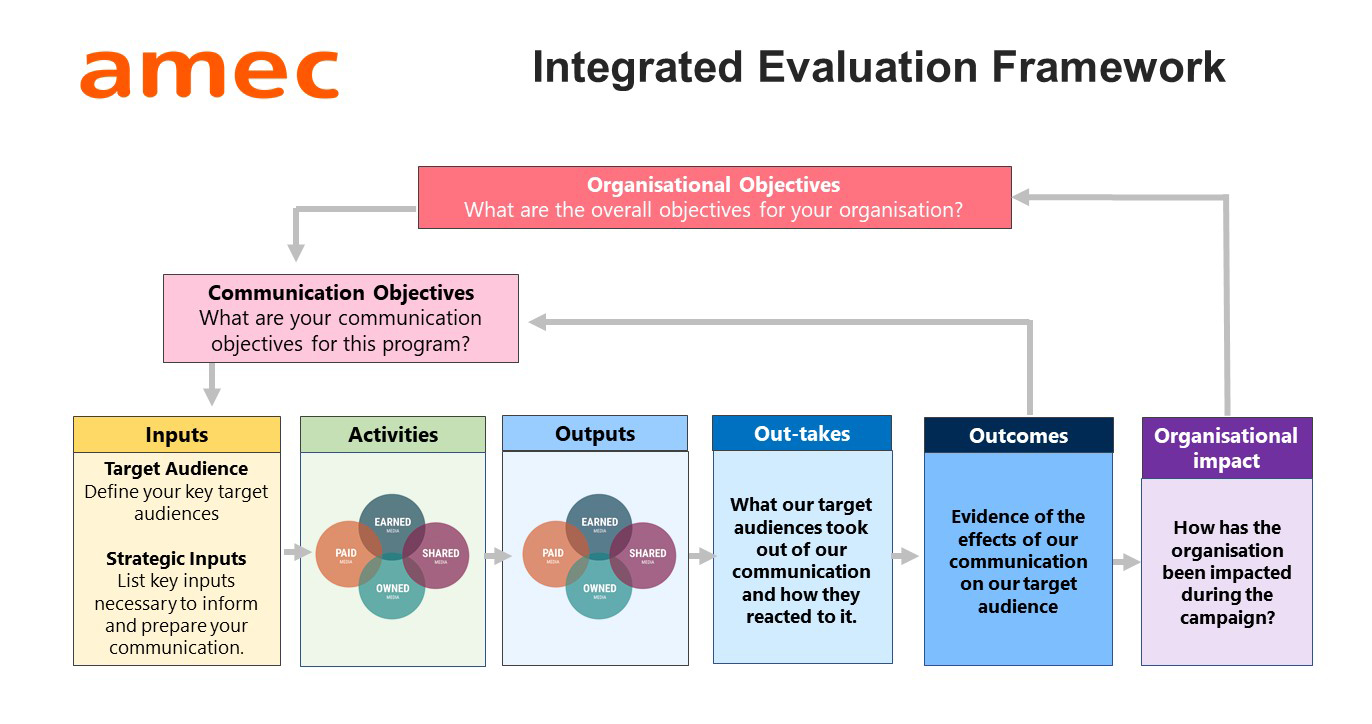

This approach to measurement and evaluation has been proposed by the International Association for Measurement and Evaluation of Communication (AMEC) since the publication of the Barcelona Principles in 2010 (updated in 2015), and more recently, with the appearance in 2016 of the Integrated Communications Measurement Framework. The framework distinguishes between Objectives (SMART ones), Output (our story and messages communicated to our target audience), Out-takes (immediate reaction of our audience and information recall of a story, organisation or product) and Outcomes (effects in the attitudes, opinion and behaviour of our audience towards a story, organisation or product). At least a version of this is worth considering for structuring an integrated communications program or campaign.

Let’s go back for a minute to the fancy-looking graphs. To clarify, these graphs with news coverage segmented by prominence, favourability, audience, reach, themes, message cut-through, visual impact, etc. do have a role, an important one even. They help us to stir a program in different directions if needed, and they might even be useful for generating KPIs. But if we’re aiming to have in place a sound strategy across all media with measurable communication objectives that can aid the organisation’s business goals, it’s critical to consider news coverage for what it is – which is, output, not outcome.

It’s also important to note for anyone that made it this far down in this cranky blogpost that a clear taxonomy of concepts is not an end in itself. The ultimate benefit of referring to news coverage for what it is is that it allows us to look at the big picture, which is first and foremost, our communication objectives. What is it that we’re trying to do? Is it increasing brand awareness among a specified segment of the market from 10% to 15% in the next 12 months? Is it to replace A for B as the most associated brand attribute, assuming A will help the organisation to increase leads or conversions? Is it to decrease from 20% to 15% the percentage of people who are currently not considering buying our products in the near future? Is it to lower from 60% to 20% in three years the amount of people with a specific misperception about our organisation and its services? All these are examples of the right questions to ask whenever communicational objectives are discussed and agreed on in writing.

Only once these communication objectives have been achieved, can we truly say that our integrated program across all media teams has jointly achieved a “very good outcome”.